Video/Audio Version:

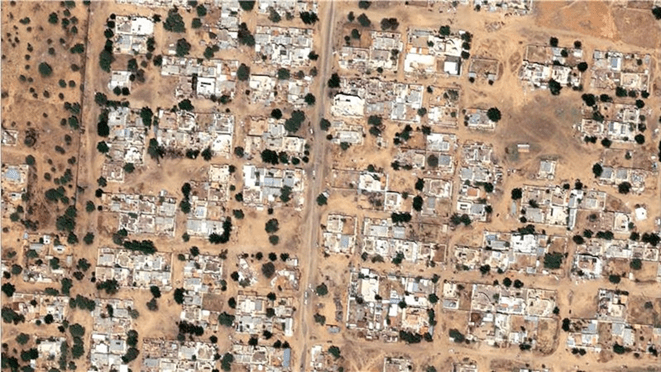

Photo Credit: Humanitarian Research Lab at the Yale School of Public Health

A Brief Background of the Conflict:

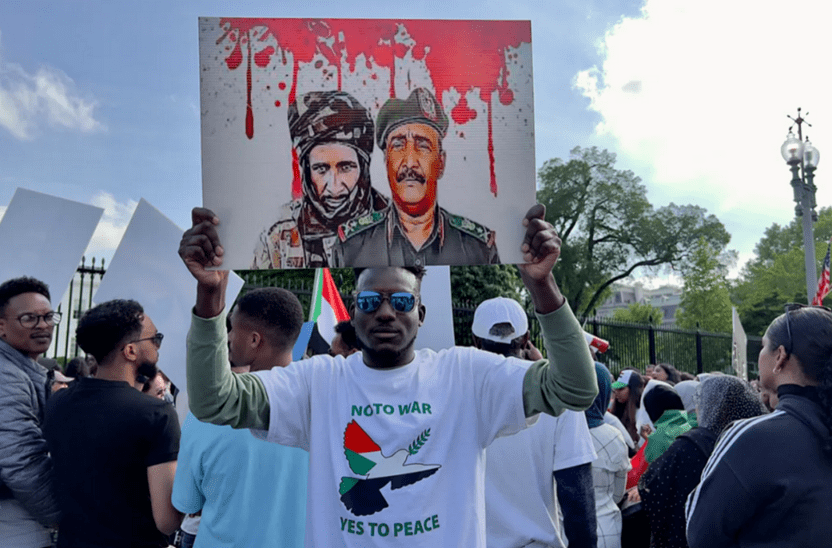

The current war in Sudan erupted on 15 April 2023, when the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) launched coordinated assaults across the country, targeting bases and key infrastructure controlled by the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF). The RSF, a powerful paramilitary organization with roots in the Darfur region, was officially established in 2013 from militia networks originally mobilized by the government to suppress insurgent groups during the Darfur conflict. The SAF, in contrast, represents Sudan’s long-standing national military institution and has historically served as the dominant actor in the country’s political hierarchy. What began as a confrontation between two security bodies has since evolved into a full-scale civil war and a struggle for control over the Sudanese state, its resources, and its political future.

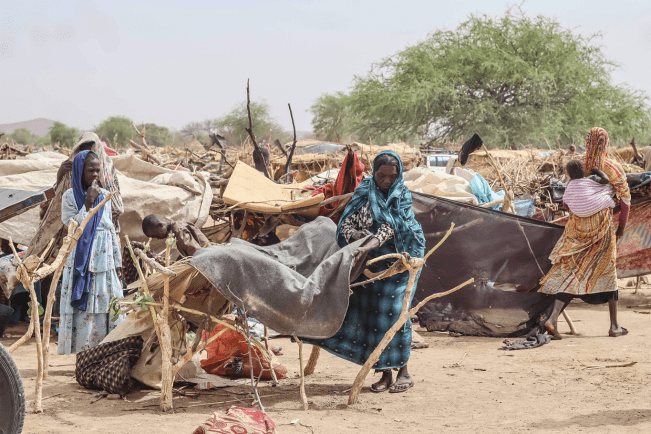

The humanitarian consequences have been devastating. Entire neighborhoods of Khartoum and other cities have been reduced to rubble, and millions of civilians have been displaced internally or forced to flee across borders. Reports of massacres, sexual violence, and the deliberate targeting of hospitals and aid convoys reveal the degree to which the conflict has eroded the foundations of civilian life. As both sides entrench their positions, Sudan has become the stage for a wider contest of international interests, where regional and global powers alike contribute to the perpetuation of violence under the guise of stability, security, and influence.

Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) Perspective:

Credit: Tariq Mohamed/Xinhua News Agency/Tariq Mohamed/Xinhua News Agency

From the SAF’s standpoint, it views itself as the legitimate national military entrusted with protecting Sudan’s territorial integrity, law and order, and sovereignty. It positions the RSF’s actions as illegitimate and destabilising (The United States Institute of Peace 2023). The SAF sees the root of the conflict in attempts by the RSF to usurp authority over the security apparatus and to avoid integration or subordination to the state army. In other words, the SAF claims the RSF wants a state-within-a-state (The United States Institute of Peace 2023). The SAF argues that failure to reform the security forces (including merging RSF into SAF) creates a dual power structure, which is dangerous for national stability. It sees itself as defending not only against the RSF but also against broader fragmentation or collapse of central authority (The United States Institute of Peace 2023).

The SAF retains air force and heavy‐weapons capabilities, though it suffers in manpower, morale, command, and logistics. It uses conventional military operations, recapturing key urban centres, air strikes, siege, and encirclement operations. For example, the SAF regained control of central Khartoum in March 2025 (Ali Et Al 2025). The SAF has also fought to cut RSF supply lines, retake major cities, and restore government control over central Sudan (Ali Et Al 2025). The SAF claims that without its operation, Sudan would slide into fragmentation, particularly given the RSF’s hold over much of Darfur and western regions.

The SAF faces historic problems, such as manpower shortages, issues of cohesion, a legacy of military regimes, and entanglement of the military in politics and economy, which complicates reform (The United States Institute of Peace 2023). The SAF is also criticized for its own share of civilian harm, obstruction of humanitarian aid, and for being part of a military-political structure that has long had poor relations with civilian populations. Human rights organisations attribute serious violations to SAF forces as well (Amnesty International N.D.). From the SAF perspective, the RSF’s mobility and ability to control territory are challenging their monopoly of force; the army fears being hollowed out or marginalized if the RSF is allowed to dominate (The United States Institute of Peace 2023).

Rapid Support Forces (RSF) Perspective

Credit: Yasuyoshi Chiba, AFP/Getty Images

The RSF claims to represent an alternative power centre, and from their perspective, the existing military and political system (in which the SAF is dominant) is unreformed, exclusionary, and needs change. They present themselves as modernising and resisting a structure that keeps them subordinate (The United States Institute of Peace 2023). The RSF argues they should not just be folded into the SAF without protections for their command structure, status, and role; their leader, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (“Hemedti”), has insisted on reforms, arguing that integration must wait until a more inclusive, professional military is established (The United States Institute of Peace 2023). The RSF also frames the conflict as one over legitimacy and a political future. They announce the formation of a parallel government and a “new Sudan” charter, positioning themselves as an alternative to the SAF-dominated order (Okello 2025).

The RSF is highly mobile, uses light vehicles, rapid maneuvers, and paramilitary-style tactics rather than conventional heavy armour. It had significant territorial control early on, especially in Darfur and western regions (Amnesty International N.D.). The RSF engaged in taking advantage of the fragility in the SAF’s structures, surprise operations in urban centres (e.g., Khartoum), and leveraged its networks (Darfur links) to secure bases in vast regions (Ali 2024). On the political side, the RSF tried to capture legitimacy by setting up parallel civil administration in areas it controls, suggesting a rival state structure (Okello 2025).

The RSF is widely criticised for human rights abuses: massacres, ethnic violence (especially in Darfur), obstruction of humanitarian assistance, and use of force against civilians (Amnesty International N.D.). It lacks some of the institutional depth and legitimacy of a national army, and questions remain about its command structure, long-term governance capability, and ability to transition to peacetime roles. From the RSF’s perspective, this might be a feature that they are a “force for change”, but from many observers, this is a vulnerability. With the SAF re-gaining momentum by 2025, the SAF seemed to “have the upper hand” in central Sudan, the RSF finds itself increasingly on the defensive in some regions (Ali Et Al 2025).

The Enduring Conflict:

Credit: Jordistock, Getty Images

At the heart of this conflict is who controls the instruments of force in Sudan. The SAF wants a unified, state-controlled military apparatus; the RSF resists subordination and wants either to maintain autonomy or dominate (The United States Institute of Peace 2023). Each side claims to be the legitimate path for Sudan’s future: SAF under Burhan (and the state) vs. RSF under Hemedti and the “new Sudan” order. This means the conflict is not just military but political, and thus harder to resolve by battlefield alone. Control of key regions, infrastructure (airports, ports, cities), and supply lines matter. The RSF has held parts of Darfur, before the SAF reclaimed central Sudan. The struggle is partly over who controls what (Ali Et Al 2025). Both sides see (and blame) the other for atrocities, civilian harm, and humanitarian access issues. This intensifies the conflict, draws in international actors, and increases the complexity of any settlement (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights 2025). Each side has external supporters or opponents. The SAF is supported (to some degree) by neighboring states concerned about stability and the RSF has been accused of having foreign backing, or at least using external resources. This external dimension complicates negotiations (Ray 2025).

Because both sides see the future of Sudan in fundamentally different ways, any settlement would necessarily require major restructuring of the security and governance system, which is very hard in a war context. The conflict is nationwide, not limited to a frontier region, as central Sudan (Khartoum), Darfur, Kordofan, etc, are all involved. That breadth makes it harder to negotiate sector by sector (United States Institute of Peace 2023). [Humanitarian catastrophe and civilian suffering are both a consequence and a driver of escalation. Atrocities on both sides provoke retaliation, spill into ethnic dimensions, and complicate peace efforts. The external actors add another layer of interest and interference, which can prolong the conflict. Finally, trust is very low. SAF fears RSF ambitions, RSF fears SAF repression. Any transition would need guarantees, but neither side fully trusts the other to abide by them.]

Key External Actors Supporting the RSF:

THE UNITED ARAB EMIRATES – GOLD, RED SEA & HORN OF AFRICA INFLUENCE

Credit: Eduardo Soteras

The UAE is widely cited as providing arms, logistics, and financial backing to the RSF (Martin 2024). The trade-off is that the RSF controls large gold-mining and extraction areas in Sudan, and the UAE gains access to gold exports, trade flows, and investment opportunities, especially through Dubai (Soliman & Baldo 2025). The UAE also has strategic interests in the Red Sea and Horn of Africa region, including influence over port infrastructure and routes; enabling a force like the RSF gives them leverage (Al-Anani 2023). For the RSF, this support means greater mobility, access to weapons, and an external patron that helps sustain operations beyond purely domestic resources. However, the involvement also helps drive the conflict’s escalation by creating external supply lines (Badi 2024).

CHAD & SOME SAHEL BORDER ACTORS – (MONEY & LOGISTICS)

Credit: News Central

The RSF is reported to use Chadian territory, air and land routes, for supply and logistics. Some reports tie Chad to RSF support (or at least to allowing RSF supply passage), often in connection with UAE interests (France-Presse 2025). [For the RSF, access through Chad broadens its operational logistics; for Chad, the alliance may earn financial or political benefits.]

WAGNER GROUP (RUSSIA) – GOLD & RED SEA TRADE ROUTES

Credit: French Military

Early in the conflict, there was strong evidence that Wagner (a Russian private military company) provided arms/training to the RSF, capitalising on RSF control of gold mines and resource flows (Abdalla 2024). Wagner had access to Sudan’s mineral wealth, and could secure a foothold on the Red Sea (especially via port deals) by backing a force like the RSF, which is more flexible and less tied to state structures (Abdalla 2024). [However, Russia’s allegiance appears to have shifted over time.]

Key External Actors Supporting SAF:

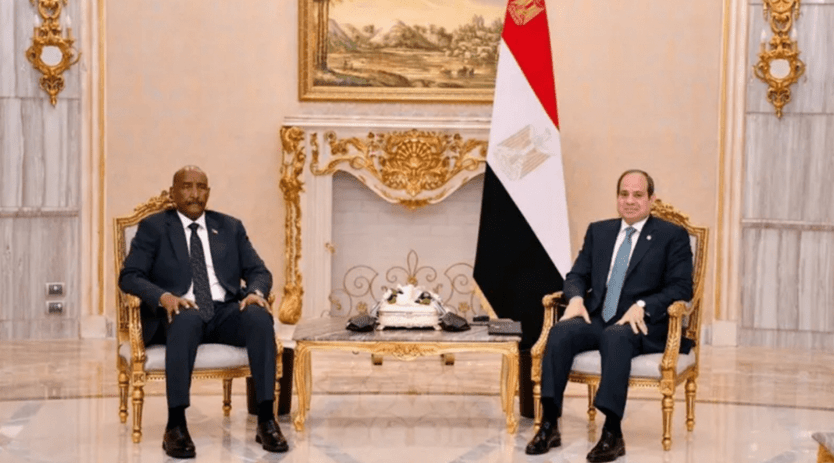

EGYPT – REGIONAL STABILITY & REFUGEE INFLOW

Credit: AFP

Egypt is frequently cited as one of the clearest backers of the SAF and General Abdel Fattah al‑Burhan’s camp (Lewis 2024). Sudan is Egypt’s southern neighbour. Egypt has strategic interests in stability (or at least predictability) across its border. Controlling refugee flows, regional security, access to the Nile, and ensuring that Sudan does not become a base for hostile actors, benefits Egypt (Donelli 2025). [For the SAF, Egyptian support gives political legitimacy, diplomatic backing, and likely material or training assistance.]

TURKIYE – GOLD & HORN OF AFRICA TRADE ROUTES

Credit: BIROL BEBEK/AFP via Getty Images

Turkiye is cited as providing weapons (including drones) and military logistics support to the SAF (Critical Threats Project 2025). Turkiye has growing ambitions in the Horn of Africa, wants to build military-commercial ties, secure port and mining deals, and counter-rival the Gulf states (e.g., UAE). Supporting the SAF helps Turkiye build those links (Critical Threats Project 2025). [This gives the SAF access to relatively modern UAV remote-sensing capability, which is significant in this conflict.]

IRAN – HORN OF AFRICA, RED SEA TRADE ROUTES & INFLUENCE

Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir in 2006.

Credit: IRNA/AFP via Getty Images

Iran is reported as supporting the SAF (or at least having cooperated with SAF in drone and military supply) (The Soufan Center 2025). [Most likely, Iran seeks influence in the Red Sea and Horn of Africa, possibly using Sudan as a back-door to project maritime or regional power, or secure trade routes. This kind of support strengthens the SAF’s ability to fight the RSF.]

RUSSIA (SHIFTED POSITION) – READ SEA TRADE INFLUENCE & MARITIME MILITARY ADVANTAGES

Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, in 2019.

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Although Wagner (Russian Mercenaries) initially appeared to support the RSF, by mid-2024, Russia was reported to have shifted to supporting the SAF (or at least the state side) because Russia’s strategic aim of securing a naval base in Port Sudan requires a government ally rather than a fragmented rebel force (McGregor 2024). [A state-partner would give Russia long-term legal and security guarantees, and controlling or influencing the Red Sea coast would give Russia a strategic maritime advantage. By aligning with the SAF, Russia hopes to ensure more predictable access. For the SAF, this shift offers a boost in heavy military support and a major external patron.]

CHINA – TRADE (PIPELINES, PORTS, RAILWAYS/THE BELT AND ROAD INITIATIVE)

Credit: Xinhua

China has been one of Sudan’s major trading and investment partners, especially in the oil, infrastructure, and construction sectors (Al-Anani 2023). Its involvement is often framed in terms of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and securing stable trade routes, infrastructure (ports, pipelines, railways), and access to resources (Nicholson 2025). According to a 2024 study, China’s foreign policy approach in Sudan has been driven by both strategic (securing material interests, stability) and reputational (global image, non-interference) factors (Wang 2024). Beijing publicly emphasises non-interference in the internal affairs of other states and calls for conflict resolution and humanitarian assistance. For example, China’s UN representative said China would “continue to provide assistance” in humanitarian supplies to Sudan (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, People’s Republic of China 2025).

While China may not publicly declare which side it supports militarily (and its official stance is relatively neutral), there is accumulating evidence that Chinese-manufactured arms and equipment have found their way into the war. Investigations have identified Chinese-manufactured guided bombs in RSF attacks in North Darfur. The report states these weapons are “almost certainly re-exported” to the RSF via the UAE (Amnesty International N.D.). Another source reports that Chinese-manufactured weapons are being used by both SAF and RSF, though without a clear breakdown of which side has how many (Ayin Network 2025). The Sudanese government has publicly demanded that China act against its technology being used by RSF (in particular, Chinese-made drones) and hold those responsible to account, accusing the RSF and the UAE of enabling such transfers (Sudan Tribune 2025). China has denied direct involvement in supplying arms to the RSF (Alnaser Et Al 2025). [For example, China’s chargé d’affaires in Sudan stated China had “no relationship” with the RSF. This has led to suspicions of double-dealing or even conspiracy.]

[China’s interests in a stable Sudan align with supporting the state apparatus (the SAF) in maintaining control, and ensuring infrastructure and investment interests aren’t subjected to complete collapse. China has strong incentives to back the SAF indirectly (through economic investment, reconstruction, and infrastructure) because disruption threatens its interests. China might tacitly allow or turn a blind eye to arms flows, or re-exports of Chinese equipment, that strengthen the SAF, even if not overtly acknowledged. But publicly, China is cautious. It emphasises humanitarian assistance and mediation rather than overt military involvement.]

China’s direct support of RSF is not clearly documented (and China officially denies supplying the RSF). However, Chinese-manufactured weapons are documented in RSF hands via third-party transfers (e.g., through the UAE), which implicates Chinese origin. So while China may not be the immediate supplier, its armament industry is indirectly involved. This means China’s weapons industry benefits financially, and by extension, China’s strategic reach is extended (albeit indirectly). China nonetheless differentiates its official relationships. Because China’s official policy emphasises non-interference, Beijing is cautious about being perceived as choosing sides in internal conflicts.

The fact that Chinese arms reach both sides means China retains flexibility- Whichever side eventually prevails, China’s equipment is there, and China’s investments remain relevant. China’s leverage, is if it pushes for peace or settlement, it can propose itself as a mediator (via its diplomatic standing) and protector of economic interests. Indeed, some have argued China is well-positioned to be a peace broker in Sudan. But China also must manage reputational risk. It can’t be seen as arming parties in a conflict with large humanitarian damages to its global image (especially given earlier criticism during the Darfur crisis). This study notes this tension: Wang 2024.

What China IS Doing:

Investing heavily in Sudan’s economy (oil, infrastructure, trade), thus tying its interests to stability; Supplying or allowing the supply of Chinese-manufactured weapons (directly or indirectly) that are in use by both SAF and RSF; And sending humanitarian assistance and publicly calling for peace, while preserving diplomatic neutrality. Using its status to potentially broker or influence peace efforts in Sudan.

What China IS NOT Doing:

Publicly declaring large-scale military support to one side (SAF) or formally allying with RSF; Taking the lead militarily or publicly in the conflict (unlike some other powers); Nor fully controlling the arms flows of its manufactured equipment once exported or re-exported. This ambiguity allows plausible deniability.

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA – HORN OF AFRICA, RED SEA INFLUENCE, TRADE ROUTES, NATURAL RESOURCES, & MILITARY LOGISTICS

Credit: Daniel Slim/AFP via Getty Images

The U.S. has strategic interests in Sudan tied to broader regional stability in the Horn of Africa and the Red Sea corridor. The U.S. also doesn’t want to leave the region to its competitors (Russia, China, and the Gulf states), so part of its involvement is about preventing rival powers from gaining unchallenged influence. The U.S. has long viewed Sudan through the lens of regional control, rather than a humanitarian concern (Hudson 2024). Sudan’s geographic position on the Red Sea gives it strategic importance for global shipping routes, military logistics, and surveillance. The U.S. seeks to prevent rival states from establishing bases there, while maintaining indirect influence through allies like Egypt and Saudi Arabia (Badi 2024). Sudan’s natural resources: gold, uranium, oil, and agricultural exports, are another point of U.S. interest. By leveraging sanctions and trade restrictions, Washington indirectly shapes which global actors can access these resources (Brundage 2025). Officially, the U.S. presents its involvement as humanitarian, promoting democracy and civilian rule, but its history in Sudan shows a recurring pattern of instrumentalizing crises for strategic and economic advantage (Fletcher 2025).

The U.S. helped design the post-2019 transitional framework that gave the military (SAF) and RSF disproportionate power in Sudan’s governance, a structure that directly collapsed into war in 2023 (Al-Anani 2023). Washington co-led the Jeddah cease-fire talks with Saudi Arabia, but critics argue they legitimized both warlords without addressing the arms flows or financial systems sustaining them (Lewis 2024). U.S. intelligence agencies have long maintained back-channel relationships with Sudanese military officials for so-called “counterterrorism cooperation,” a legacy of post-9/11 policy that blurred lines between security coordination and complicity in repression (Burndage 2025).

U.S. sanctions policy toward Sudan, active since 1997, crippled the formal economy and pushed Sudan’s elites toward smuggling, militarization, and paramilitary finance networks. These same networks now sustain the SAF and RSF (US Department of the Treasury, Office of Foreign Assets Control 2023). While publicly condemning the conflict, Washington continues to supply arms to regional partners (Egypt, UAE, and Saudi Arabia) who funnel weapons, fuel, and funds to opposing sides in Sudan (Badi 2024). The U.S. has not sanctioned the UAE or Egypt, though, despite clear evidence of their role in arming the RSF and SAF, respectively, revealing the double standard of selective enforcement (Hudson 2024).

[It’s like the United States deliberately engages in the destabilization of entire regions, creating the very conditions that give rise to terrorism. Then, when chaos ensues, the U.S. government turns around and uses those same crises to justify more wars, manufacturing public consent for endless military intervention. Meanwhile, these perpetual wars serve one primary purpose: to enrich a billionaire class that grows fat and powerful from the blood and sacrifice of our sons and daughters, who are sent to die in conflicts that should never have happened in the first place. Back home, ordinary Americans struggle in poverty and hardship, while the wealthy elite funnel our hard-earned tax dollars, the literal product of our blood, sweat, and tears, into a toxic cycle of war profiteering. This is the military-industrial complex at work: a system built on depravity, inhumanity, and the ruthless exploitation of human lives across the globe. But, let’s continue…]

The U.S. remains one of Sudan’s top aid donors, but much of that assistance is channeled through U.S.-contracted NGOs and international agencies, keeping funding under American influence (Booth 2025). Critics argue that humanitarian aid is used to leverage policy concessions, tying food and medical assistance to cooperation with U.S.-aligned political frameworks (Al-Anani 2024).

The U.S. continues to recognize General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and the SAF as the official government despite the military’s own record of atrocities, including airstrikes on Khartoum civilians (Al-Jazeera Staff 2023). [The truth is, both the SAF and RSF are drenched in blood, and the chaos only serves the superpowers. The U.S., Russia, and China all exploit the conflict to protect the power, influence, and profits of their oligarchs.] U.S. military coordination with Egypt, the SAF’s primary external backer, effectively supports SAF operations through intelligence sharing and logistics (Sharp 2025). While Washington has sanctioned some SAF-linked companies, it has stopped short of targeting the leadership, and avoiding measures that could disrupt U.S. relations with Cairo or Riyadh (Hudson 2024).

On the other hand, the U.S. formally declared RSF actions in Darfur as genocide and sanctioned Hemedti’s gold-trading networks (Bowen 2025). However, much of the RSF’s weaponry originates from UAE stockpiles filled with U.S.-made systems, illustrating how Washington’s own arms exports indirectly [but likely intentionally] feeds the paramilitary side it condemns (Amnesty International N.D.).

[The U.S. claims it has moral authority but shows it has selective accountability. It condemns atrocities while maintaining defense contracts with the very governments arming Sudan’s belligerents. By structuring Sudan’s post-Bashir transition around military power-sharing, Washington inadvertently cemented the SAF-RSF rivalry that exploded into civil war. Sanctions against Sudan have a dual effect, they isolate the government while driving it toward alternative patrons like Russia or Iran, thereby perpetuating the cycle of proxy wars. U.S. “peace efforts” often serve to maintain influence, ensuring continued Western access to the Red Sea, not to end violence.]

What the USA IS Doing:

Providing humanitarian aid while using it as diplomatic leverage; Imposing selective sanctions on RSF and SAF-linked businesses; Maintaining close military ties with Egypt and Saudi Arabia, both key players in Sudan’s war; And publicly denouncing atrocities while sustaining economic and arms relationships with those indirectly fueling them.

What the USA IS NOT Doing:

Confronting the role of its allies in prolonging the war; Halting its own weapons exports that empower regional belligerents; Offering consistent civilian-led reconstruction support unlinked to Western strategic priorities; Nor taking responsibility for policy decisions that militarized Sudan’s post-revolution landscape.

Final Thoughts…

Credit: Gueipeur Denis Sassou/Agence France-Presse, Getty Images

The war in Sudan is not merely a domestic power struggle between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF); it is a mirror reflecting the competing ambitions of powerful external actors whose involvement has deepened and prolonged the conflict. Egypt’s military and logistical backing of the SAF stems from its desire to control the Nile corridor and secure its southern border, while the United Arab Emirates finances and arms the RSF through gold trading networks to expand its regional influence and access to Sudan’s mineral wealth. Saudi Arabia walks a delicate line, funding humanitarian initiatives while quietly supporting the SAF to maintain stability along the Red Sea. Turkiye, Iran, and Russia have each sought to use Sudan to expand their strategic footprints: Turkiye through defense exports, Iran through drone and surveillance support, and Russia first via Wagner’s gold mining and later through alignment with the SAF to secure a naval base at Port Sudan. China’s involvement is primarily economic, anchored in infrastructure investment and arms manufacturing, but its exports and trade indirectly sustain both warring sides.

The United States positions itself as a peace broker, yet its long record of militarization, sanctions, and proxy alliances makes it deeply complicit in Sudan’s ongoing tragedy and genocide. The United States cannot be absolved of complicity. Decades of sanctions, selective diplomacy, and arms sales to its regional allies have helped militarize Sudan’s politics and sustain the war economy. By continuing to arm and finance partners such as Egypt and the UAE, both directly involved in the fighting, Washington’s hands are bloodied alongside those of the powers it criticizes.

Together, these external actors have transformed Sudan into a proxy battleground where global rivalries eclipse the suffering of its people. The ongoing devastation is not only the product of Sudanese factionalism but of an international system that treats fragile nations as chessboards for power. While Sudanese generals pull the triggers, foreign powers load the guns. Until the global patrons who arm, fund, and exploit both the SAF and the RSF withdraw their influence, peace in Sudan will remain an illusion.

Resources

Abdalla, S. (2024). Emerging Stage for Great Power Competition: Russia’s Influence in Sudan Amid Political Turmoil. Security in Context. https://www.securityincontext.org/posts/emerging-stage-for-great-power-competition-russias-influence-in-sudan-amid-political-turmoil

Al-Anani, K. (2024, May 11). The Sudan Crisis: How Regional Actors’ Competing Interests Fuel the Conflict. Arab Center Washington DC. https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/the-sudan-crisis-how-regional-actors-competing-interests-fuel-the-conflict/

Ali, H. (2024). The War in Sudan: How Weapons and Networks Shattered a Power Struggle (GIGA Focus Middle East, No. 2). German Institute for Global and Area Studies. https://www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus/the-war-in-sudan-how-weapons-and-networks-shattered-a-power-struggle

Ali Mahmoud Ali, Getachew Birru, & Eltayeb Nohad. (2025, April 15). Two Years of War in Sudan: How the SAF is Gaining the Upper Hand. Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). https://acleddata.com/report/two-years-war-sudan-how-saf-gaining-upper-hand

Al Jazeera Staff. (2023, June 1). US Imposes First Sanctions Over Sudan Conflict. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/6/1/us-imposes-first-sanctions-over-sudan-conflict

Alnaser, H., Idris, M., Alagra, M., & al-Faroug, O. (2025, May 3). Sudan Nashra: Burhan, Sisi Discuss Military Cooperation | RSF Captures Nuhud, West Kordofan | Burhan Appoints Ambassador to Saudi Arabia as Acting Prime Minister. Mada Masr. https://www.madamasr.com/en/2025/05/03/news/u/sudan-nashra-burhan-sisi-discuss-military-cooperation-rsf-captures-nuhud-west-kordofan-burhan-appoints-ambassador-to-saudi-arabia-as-acting-prime-minister/

Amnesty International. (n.d.). Destruction and Violence in Sudan. https://www.amnesty.org/en/projects/sudan-conflict/

Ayin Network. (2025, June 3). China’s Hidden Hands: How Chinese Weapons are Fueling Both Sides of Sudan’s War. https://3ayin.com/en/china/

Badi, E. (2024, December 17). Sudan is Caught in a Web of External Interference: So Why is the UAE Intervening? Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/sudan-rsf-saf-uae-intervention/

Booth, D. E. (2025, February 19). A Bolder US Approach for Ending the War in Sudan: Addressing Key Threats and Identifying Interests. Wilson Center. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/bolder-us-approach-ending-war-sudan-addressing-key-threats-and-identifying-interests

Bowen, J. (2025, January 7). US Declares Sudan’s Paramilitary Forces Committed Genocide During Civil War. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/jan/07/us-determines-sudan-paramilitary-genocide

Brundage, W. (2025, August 6). The Case for U.S. Involvement in the Sudanese Civil War. New Lines Institute. https://newlinesinstitute.org/political-systems/the-case-for-u-s-involvement-in-the-sudanese-civil-war/

Critical Threats Project. (2025, April 15). Sudan’s Civil War: Global Stakes, Local Costs (Africa File). https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/africa-file/sudans-civil-war-global-stakes-local-costs

Donelli, F. (2025, May 6). Sudan’s Civil War and the Gulf Chessboard. Orion Policy Institute. https://orionpolicy.org/sudans-civil-war-and-the-gulf-chessboard/

Fletcher, H. B. (2025, February 3). The Sudan War and the Limits of American Power. Lawfare. https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/the-sudan-war-and-the-limits-of-american-power

France-Presse, A. (2025, October 31). Global Proxy War: Which Foreign Powers are Backing Sudan’s Warring Generals. NDTV. https://www.ndtv.com/world-news/global-proxy-war-which-foreign-powers-are-backing-sudans-warring-generals-9550320

Hudson, C. (2024, July 11). Washington is Becoming Irrelevant in Sudan: A Sanctions Strategy Could Change That. Center for Strategic and International Studies. https://www.csis.org/analysis/washington-becoming-irrelevant-sudan-sanctions-strategy-could-change

Lewis, A. (2023, April 12). Sudan’s Conflict: Who is Backing the Rival Commanders? Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/sudans-conflict-whos-backing-rival-commanders-2023-05-03/

Lewis, A. (2024, April 24). US Urges All Armed Forces in Sudan to Halt North Darfur Attacks. Reuters. Lewis, A. (2024, April 24). https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/us-urges-all-armed-forces-sudan-halt-north-darfur-attacks-2024-04-24/

Matin, I. L. (2024, November 16). Civil War in Sudan: External Actors Profiting from the War. Global Affairs and Strategic Studies, University of Navarra. https://en.unav.edu/web/global-affairs/guerra-civil-en-sudan-agentes-externos-que-sacan-provecho

McGregor, A. (2024, July 8). Russia Switches Sides in Sudan War. The Jamestown Foundation. https://jamestown.org/program/russia-switches-sides-in-sudan-war/

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. (2025, Februrary 27). Remarks by China’s Permanent Representative to the UN Ambassador Fu Cong at the UN Security Council Briefing on Sudan. https://www.mfa.gov.cn/eng/xw/zwbd/202503/t20250304_11567849.html

Nicholson, F. (2025, May). Unpacking the New Face of Conflict: Sudan’s Civil War Amid a Fragmented Geopolitical Order. Vision of Humanity. https://www.visionofhumanity.org/unpacking-the-new-face-of-conflict-sudans-civil-war-amid-a-fragmented-geopolitical-order/

Office of Foreign Assets Control, U.S. Department of the Treasury. (2023, July 25). An Overview of the Sudanese Sanctions Regulations: Title 31 C.F.R. Part 538 and Executive Order – Blocking Property of Persons in Connection with the Conflict in Sudan’s Darfur Region [Fact sheet]. https://ofac.treasury.gov/media/18346/download

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. (2025, June 17). Sudan: War Intensifying with Devastating Consequences for Civilians, UN Fact-Finding Mission Says. https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2025/06/sudan-war-intensifying-devastating-consequences-civilians-un-fact-finding

Okello, M. C. (2025, May 16). Could Prolonged Warfare in Sudan Split the Country? Genocide Watch. https://www.genocidewatch.com/single-post/could-prolonged-warfare-in-sudan-split-the-country

Ray, C. A. (2025, July 2). Foreign Influence is Fueling the War in Sudan. Foreign Policy Research Institute. https://www.fpri.org/article/2025/07/foreign-influence-is-fueling-the-war-in-sudan/

Sharp, J. M. (2025, June 12). Egypt: Background and U.S. Relations (CRS Report No. RL33003). Congressional Research Service. https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/RL33003

Soliman, A., & Baldo, S. (2025, March 26). Gold and the War in Sudan: How Regional Solutions can Support an End to Conflict. Chatham House. https://www.chathamhouse.org/2025/03/gold-and-war-sudan/summary

The Soufan Center. (2025, March 26). IntelBrief: The Sudan Crisis and the Gulf Chessboard. https://thesoufancenter.org/intelbrief-2025-march-26/

Stigant, S. (2023, April 20). What’s Behind the Fighting in Sudan? United States Institute of Peace. https://www.usip.org/publications/2023/04/whats-behind-fighting-sudan

Sudan Tribune. (n.d.). Sudan Demands China Act Against RSF Drone Use, Accuses UAE. https://sudantribune.com/article/300914

Wang, G. S. (2024, September 23). What Motivates Chinese Foreign Policy in Sudan? A Discourse Analysis of Chinese Official Statements on the Darfur Conflict from 2004 to 2023. The Grimshaw Review of International Affairs, 1(2). https://grimshawreview.lse.ac.uk/articles/10